Genesis, 18:1-22:24

This Week’s Torah Portion | October 29 – November 04, 2017 – 9 Cheshvan – 15 Cheshvan, 5778

In A Nutshell

The portion, VaYera (The Lord Appeared), begins with the story of the three angels that came to Abraham and told Sarah she would have a son. Sarah laughed because she could not believe that she would have a son at her age. Yet, she did have a son, whose name was Ytzhak (Isaac) named after her Tzhok (laughter).

The angels continued on their way to destroy the cities, Sodom and Gomorrah, due to the many sins being committed there. Lot and his family were allowed to escape, but Lot’s wife did not obey the angels’ orders, turned around to look, and became a pillar of salt. Lot and his two daughters made it to a cave. Lot’s daughters were certain that they were the only survivors in the world, so they tricked their father into having children with them.

Later in the portion, following Sarah’s request, Abraham expels Hagar and Ishmael to the desert; the Creator commands Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, and in the last moment, an angel stops the execution. Abraham takes a ram that he found caught in the thicket and offers it instead of his son.

Commentary by Dr. Michael Laitman

In “A Preface to the Book of Zohar,” one of Baal HaSulam’s introductions to The Book of Zohar, he offers a special explanation of our perception of reality. The explanation details how we perceive the reality we live in, and how the place where we are is depicted in us as an image of emotions, which are portrayed as solid, as gas, as liquid, etc.

The Zohar and the wisdom of Kabbalah explain that due to the way in which we perceive reality—with our qualities and senses—we react to something outside of us, which we do not know, and which we turn into various colors and materials. However, we need to acquire additional senses and rise to a higher perception of reality, above our senses. This is how we will discover the upper world.

The Book of Zohar speaks to us in the “language of the branches,” using the terms of our world. It tells us how we can obtain and be impressed with the new form, which is higher than our world. Sometimes our concepts seem real to us, such as a pillar of salt, the upheaval of Sodom and Gomorrah, or the story of the three angels, etc., since “a verse does not extend the literal” (Masechet Yevamot, 24a). Yet, we should strive to see these concepts as relationships between us in the common soul.

The events of the portion are not merely historic tales; they are sources that deal with the connections between us. The role of these sources is to teach one who wishes to advance and rise to the new perception of reality how to scrutinize one’s desires, qualities, forces, and the connections between them, in order to design from them the perception of reality that is called, for instance, “the portion, VaYera.”

With each portion, we must rise higher until we arrive at the entrance to the land of Israel, where all our desires aim to bestow, in Dvekut (adhesion), so we may begin the actual work. The Torah reveals to us the light that reforms so we may advance from the reception of the Torah to the entrance to the land of Israel—a state where we can work with the entire substance of creation—with all of our desires—in the proper way. The word Eretz (land) comes from the word Ratzon (desire), and the word Ysrael (Israel) comes from the words Yashar El (straight to God).

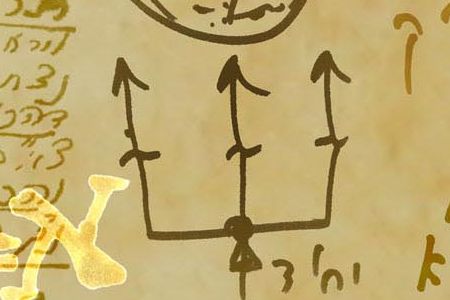

The three angels are three forces that exist within us: right, left, and middle, through which we advance. There is the Abraham within us; this is the right line. On the one hand, he has the Klipa (shell/peel) of the right, who are Hagar and Ishmael, and on the other hand, he has the Klipa of the left, who are Isaac and Esau, with whom we attain the middle line, who is Jacob, at the conclusion of the process of correction.

A person sorts all of one’s mental forces out of the qualities that aim toward giving, and out of the qualities that aim toward receiving. In the middle, between them, is the balanced combination of the forces: the force of Hesed (mercy)—right—is Abraham, and the force of Gevura—left—is Isaac, while the forces of the angels are Michael on the right, and Gabriel on the left.

We need to sort the depth of the desires with which we can work because we cannot work with all our desires in order to bestow. Although each Mitzva (commandment) along the way aims toward “love your neighbor as yourself,” I still need to sort out all my desires and see whether I can achieve love of others with them. If I cannot, I avoid using them until the next, better state.

This is why Abraham had to cut—some to the right and some to the left—as in the case of the strife between the herdsmen of Lot’s cattle and the herdsmen of his cattle, where it was quite clear who was to the right and who was to the left. In a state of Sodom, there is a mixture once again, which behooves a similar scrutiny.

On the one hand, Lot must be taken out of there. On the other hand, Lot’s “female” desire must be removed. A male is the force of bestowal, while a female is the force of reception. Therefore, following the scrutiny, since it was not possible to work with Lot’s desire, his wife became a pillar of salt. We use salt to add flavor to our feed. Without it, our food would be tasteless; but we use it only on condition that it’s lifeless. Water is a state of semi-dead, semi-living. Salt, which is essentially one mineral, is extracted from the ground when it is completely lifeless; it is neither a vegetable nor an animal.

This is the way one scrutinizes more and more degrees. In the tying of Isaac we scrutinize how to tie up the left line, how to prevent it from using its powers to the fullest. Abraham, the force of the right, holds the left line and binds it, preventing it from being used. He does it by cutting out his own animal part, but leaving his speaking part. The rest can be sacrificed as an offering.

Another form of scrutiny is through deportation of the part of the right that cannot join the left. This manifests in the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael. Through serious inner work, a person scrutinizes with which forces of the soul it is possible to work and to advance from portion to portion, from degree to degree.

Concerning our time, the Sodom and Gomorrah issue resembles the American approach, which says, “let mine be mine; let yours be yours.” In other words, there is democracy, and there is freedom of the individual, and each one is to oneself. Clearly and unequivocally, we do not come into a connection where I am for you and you are for me. There is no emotional commitment, help, or bonding. It is just as it was in Sodom and Gomorrah.

Right from the start we are told that if we want to advance on the path of correction of the soul, we need to change how we relate to one another. The relationship must be oriented toward connection. “Let mine be mine; let yours be yours” is Sodomite rule. Even if it seems to us that it is a respectable attitude when no one messes with one’s neighbors business, that attitude contradicts the purpose of creation, which is to be “as one man with one heart” (RASHI, Exodus, 19b), to unite into a single system. This is why today Nature is presenting us with an integral, circular system where we are all inevitably connected, the complete opposite of Sodomite rule.

The portion, VaYera, teaches us what we can elicit from the quality of Sodom, even if Lot’s wife, her two daughters, and Lot himself stand in our way. It does not matter that we will have to continue to correct them in relation to their sins in the cave. What matters is that right at the start of our correction we must abandon the rule, “let mine be mine; let yours be yours.”

Today the world is in precisely the same situation. This is why we must determine to destroy the previous relations between us, which were based on money, on the egotistical connection of give and take. Instead, we must fashion a system that is similar to the integral system that is currently appearing worldwide, a system where we are interdependent. Our dependence is similar to that of a family, where there are no monetary calculations, but rather emotional ones, where we draw closer to each other and become “as one man with one heart.”

Today, Sodomite rule, “let mine be mine; let yours be yours,” characterizes the fall of both communism and capitalism. We are not in a state of “Give what you can and take what you need,” as the communist proclaimed.

We are in a process where we must exit Sodom without destroying it altogether. Rather, we must overturn and rebuild it from the previous discernments, since no redundancy was created in the world. Even what seems to us as the worst possible thing can turn to good, depending on how we use it. For example, a poisonous snake is the symbol of medicine. We use the venom to produce many medicines. It is written in The Book of Zohar that when the dear wants to give birth to the soul, the serpent comes and bites her, and only then does she deliver. It is impossible to give birth to anything—neither to a new degree nor to a new soul—without the serpent’s bite.

Today we are in a very special situation, a tipping point, an inversion we must go through. It is just as there is an inversion in childbirth from a position where the head of the fetus turns upward to a position where its head turns downward. This is how we emerge from world to world. That inversion symbolizes our attitude toward the world, to people; everything becomes inverted.

This is also the inversion of Sodom and Gomorrah, which we must go through, in our relationships—from “let mine be mine; let yours be yours.” If we recognize it and willingly understand it, we will go through it easily. Otherwise, we will experience it as affliction by Nature’s forces.

Currently, the Torah is compelling us to relate to others by the rule, “that which you hate, do not do to your neighbor” (Masechet Shabbat, 31a). We must be very clear about this attitude, and not mistakenly compare it to Sodomite rule, “let mine be mine; let yours be yours.”

“That which you hate, do not do to your neighbor” does not mean that you only avoid harming others. Rather, it means you must relate to the other, so that you cannot harm another despite your ego and your will to receive. This attitude is called “desiring mercy.” Yet, this is still not an attitude of love. Rather, it is as old Hillel said to the gentile—one who wishes to draw nearer to the truth—this is only the first part, said on one leg. In the next stage, as Rabbi Akiva says, we treat others in a manner of “love your neighbor as yourself” (Jerusalem Talmud, Nedarim, Chapter 9, 30b). These are the two stages, out of which we must now execute at least the first.

It is therefore clear that the world is beginning the path of correction coercively, feeling the shattering, the crisis, and the problems. These are the days of the Messiah, in which a new world is being born before us.

The state of Sodom and Gomorrah, of “let mine be mine; let yours be yours,” seems better than our current situation. At least in Sodom people did not steal from one another. Are we really in a worse situation than in Sodom?

Our situation is far worse than in Sodom and Gomorrah. The western ideology of “let mine be mine; let yours be yours,” which says, “Do not interfere with others’ businesses—stressing the privacy and freedom of the individual—is what created this truly adverse situation. We need to get passed it and move on. Our progress toward the new world is mandatory, behooved by Nature.

Do we need to feel others in order to advance to the new world?

It is the very reason why we passed through the stage of the desert. The entire forty years in the desert were stages where we ascended above our egos, trying not to be bad to one another. This manifested in all the sins that the children of Israel committed in the desert. Each sin had its own correction, repeatedly and ceaselessly.

In this process, the disclosure of the big and corrupt desires—above which the children of Israel ascend, “that which you hate, do not do to your neighbor”—is the beginning of everything. This is how we must deal with the rest of the world. It is a very difficult task because we must rise above our desires, above our nature.

Why did the Creator command Abraham to slaughter his son?

Slaughtering refers to slaughtering one’s approach to life, which is to enjoy the world. To enjoy it means to enjoy exploiting the world.

Do you mean enjoyment at the expense of others?

I always compare myself to others, everything that I will have to ruin inside of me, and what I will build as a completely new attitude toward others.

And God Tested Abraham

“It certainly should have said Abraham, for he needed to be included in the Din because previously, there was no Din in Abraham and he was all Hesed. But now water became mingled with fire, Hesed with Din. Thus far, Abraham was incomplete, and he was crowned to pass judgment and correct the Din in its place, since there is illumination of Hochma only in the left line. Hence, before Abraham was included in Isaac, left line, he was incomplete, meaning he lacked illumination of Hochma. And through the tying, Isaac was mingled and was thus crowned with illumination of Hochma and was completed. This is why it writes that in the tying, he was crowned to pass judgment, and thus the Din was corrected, meaning the illumination of the left in its place, when he was included in Abraham’s place, in Hesed.”

Zohar for All, VaYera (The Lord Appeared), item 490

It seems that there is a problem here from the perspective of creation in relation the Creator. On the one hand, the Creator needs to create something outside of Him, a Nivra (creature), from the word Bar (outside) of the degree. On the other hand, to do good to the creature, the Creator must elevate it to a degree where the creature is exactly like the Creator, in every way. How then can these opposites merge into one in a person who is similar to the Creator, though not identical?

To do that, there is a need to create in man all the desires whose nature is opposite from that of the Creator. The 613 desires in man are then built through the 613 lights of the Torah, which are called “613 ways of the Torah.” When one begins to work with those desires, to receive in them in order to bestow upon the Creator, this is when one corrects oneself and receives in order to bestow, which is actual bestowal.

It follows that we must undergo extensive corrections once we rise above those desires we refrain from using. This is the beginning of Abraham’s correction in relation to Isaac. The scrutiny is done by the middle line—how much it is possible to receive from it, and how much it is not possible. In other words, as we ascend on the ladder of degrees we constantly scrutinize our use of the will to receive, as much as possible, in order to bestow.

Yet, it is clear to us that we have desires called “Lot’s wife,” which we must “put on hold.” Salt does not become spoiled; it can be used after a long time. This is also how we use all the discernments in us, all of our desires.

Along the way, we perform a kind of covenant—circumcision, exposing, and the drop of blood.” We do not use the biggest desires in the soul, the foreskin, but leave them for the end of correction, when we will have the strength to use them correctly—so as to do good to others. If we use them now we will only harm others. Therefore, we make all the corrections in between, called “Lot’s wife.”

A woman is the will to receive, the ego in a person. It is poised toward the desire to bestow, which can be connected to the will to receive, called “Lot and his wife.” Lot is the desire to bestow. However, the will to receive cannot work with it, which is why a person must temporarily “freeze” it, and the desire to bestow seemingly “rides over it” until the next degrees when it wakes up.

I understand that there isn’t a word of the Torah that is speaking of our world. In other words there was never an exodus from the county Egypt etc . What about in the stories of the tanakh are they also coded. For example the temple in Jerusalem we know existed only from the stories in the tanakh. If it’s all code then how do we know at all there was really a temple. Also in the case of Abraham being buried in Hebron. We only know this as historical fact from the Torah. And did King David really exist or are the stories of David also speaking of something in the spiritual world? In other words my question is there anything in the Torah or tanakh that actually refers to historical events?