Exodus, 30:11-34:35

This Week’s Torah Portion | February 9 – February 15, 2014 – Adar I 9 – Adar I 15, 5774

In A Nutshell

The portion, Ki Tissa (When You Take), begins with a request of each one of the children of Israel to donate half a shekel for the building of the tabernacle. The portion mentions some other details about the tabernacle such as the anointing oil, the table, and the menorah and its vessels, appointing Bezalel, son of Uri Ben Hur, as chief craftsman, Ahaliav Ben Ahisemech as his assistant, and commanding the children of Israel to observe the Sabbath.

Later, Moses ascends to Mount Sinai to receive the tablets of the covenant but delays in his return, so the children of Israel seek proof that the Creator exists and demand of Aaron to build a golden calf. Aaron agrees, takes their gold vessels, melts them, and builds the golden calf.

When Moses returns from the mountain and sees it, the tablets of the covenant break. The Creator wishes to destroy and ruin the entire people of Israel, and Moses pleads for their souls.

Moses speaks to the Creator “face to face,” and wishes to conceal himself.

At the end of the process, the Creator agrees and makes a covenant with the people of Israel. The Creator also promises Israel that they will enter the land of Israel, and repeats the commandment of the three Pilgrimage festivals (Shalosh Regalim) and the prohibition of idolatry.

Moses stays with the Creator on Mount Sinai forty days and forty nights, writes on the tablets, and comes down from the mountain. It is written, “And it came to pass when Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tables of the testimony in Moses’ hand … that Moses did not know that the skin of his face beamed while He talked with him” (Exodus, 34:29). It was so much so that he had to hide himself from the people once more because they feared speaking with him.

Commentary by Dr. Michael Laitman

Those who do not know the language of Kabbalah will find it hard to understand that the text actually discusses a person’s inner development. It concerns our nature, which is the will to receive, an egoistic desire that requires correction. The Torah speaks only of the correction of the desire, as it is written, “I have created the evil inclination; I have created for it the Torah as a spice”[1] because “the light in it would reform them.”[2]

The purpose of the correction is to transform our evil (egoistic) inclination, which aims only toward self-gratification and exploitation of the entire world for itself, and turn it into love of others, as in “love your neighbor as yourself.”[3]

The Torah speaks of a process that is not simple, but which all of us experience. The general crisis we are in will cause us to come out to the light, to correction, similar to the exodus from Egypt. Today we are all standing before Mount Sinai with a huge ego, with all the Kelim (vessels) we have taken from Egypt. During the millennia of development, humanity has accumulated a massive ego; now we have no clue what to do with it, other than escape it.

When we are drawn toward Mount Sinai we discover a mountain of hate between us. Only the point within us, called Moses, pulls us forward toward connection with something higher, a higher degree—human degree of similarity with the Creator.

We are all still as beasts,[4] operated entirely by egos, our nature. Instead, we must be as a free nation in our country, free in its will. “Such is the way of Torah.”[5]

To do that, one who wishes to ascend to the human degree, and discover the Creator and the worlds around us must follow the unique line known as “half a shekel,” meaning neither to the right nor to the left, but the joining of the two. The will to receive, too, takes part because it is “help made against us” (Genesis, 2:18), and against it you need the reforming light.

We have two lines: on the left is the will to receive; on the right is the light. The more we combine them, the more we correct the will to receive to similarity with the light—working in order to bestow. It is written, “And the night will shine as the day; darkness as light” (Psalms, 139:12). This is how we advance. This is the first correction—no more and no less, but precisely half. We advance when we achieve that correction, that method of advancement.

Subsequently, the tabernacle and its vessels must be prepared, including the oil and all that comes with it. The role was given only to Bezalel. Bezalel within us is that which is Betzel El (in the shadow of God), under the shadow of the Creator. Bezalel replicates the qualities from the Creator, who appears to him, and this is why he is called “wisehearted.” He knows the right combination between the heart, the desire, and the wisdom, namely the intellect. Bezalel properly combines the right with the left, and has wisdom of the heart. This is why he is the one who can establish the tabernacle.

The tabernacle is the arrangement of the soul that we build within us from our 613 desires. It is built according to the right qualities, in which all the parts are connected in synchrony with the Creator. This is how we become similar to Him.

Our evil inclination has 613 qualities we must aim in order to bestow, toward love of others. Only those who have the quality of Bezalel—copying the qualities of the Creator onto oneself and becoming as His shadow—can do it.

Achieving this is done by connecting to the Shechina (Divinity), Malchut of Atzilut, who begins to replicate these qualities from Zeir Anpin of Atzilut. Zeir Anpin has six Sephirot: Hesed, Gevura, Tifferet, Netzah, Hod, and Yesod, where Malchut comes last and replicates. This is why our work is to replicate these six qualities from Zeir Anpin—called HaKadosh Baruch Hu (The Holy One, Blessed Be He), or Zeir Anpin of Atzilut—in the appearance of the Creator on all the workdays.

The wisdom of Kabbalah presents our goal—the revelation of the Creator to the creatures in this world. Through our senses, when the Creator is revealed to us, we join and increasingly attach ourselves to the Creator.

When we conclude replicating the six qualities comes the concluding seventh quality, the Sabbath. The Sabbath concludes itself by itself from above. This is why it is considered “awakening from above.” A special light comes and sets the six qualities in the right order, and there is nothing more we need to do.

This is why the prohibition on working during Sabbath is tantamount to intervening with something that belongs to the upper light. We work for six days setting up the right and left lines, directing the will to receive and the light, the mind and the heart. Finally, we present our work, and then “The Lord will conclude for me” (Psalms, 138:8). This is when we receive the completion of the degree. This is the process we must undergo through the correction of the entire soul, week by week until we conclude the six thousand years.

We must also consider that our soul consists of desires from the evil inclination that cannot be spotted by ordinary scrutiny. They require special examination that only the golden calf can make.

Although the Torah presents it in this way, the golden calf does not represent a fall or a decline, nor does it blame anyone. Any person who experiences this process must go through all the descents and falls, just as it happened with Pharaoh in Egypt, and with the children of Israel in the desert after the events of Mount Sinai.

Even when we move from Mount Sinai to the forty years in the desert we will continue to experience states that seem negative. Each time uncorrected desires surface, we “fall” into them, so we have no choice but to discover them and correct them. It is written, “There is not a righteous man on earth who does good and will not sin” (Ecclesiastes, 7:20), or “A person does not comprehend words of Torah unless he has failed in them.”[6] Thus, first we must fail, scrutinize the failure and correct it, and then we are guaranteed to not repeat it. We are guaranteed to be kept because that desire has already been corrected into having the aim to bestow through which we progress toward love of others.

When we discover that despite the work we have done, we have not revealed the Creator, it is considered that Moses did not return from Mount Sinai. That is, we are drawn back to the intention to receive, the egoistic desire, called “the golden calf.”

Our corrupted desires are called “mixed multitude.” They ask, “Where did Moses go?” They claim we must keep going as we understand it, within us, following our reason and intellect, instead of above reason.

When we return to working within reason we are delighted. It seems to us that this way we understand and feel everything. We may not be ascending to higher degrees, but at least we are in a world that suits our egos. It is a very appealing state. We can see for ourselves how difficult it is to explain to people what nature is compelling us to do now, what is the method of correction and how we can rise to the next level. The Creator, nature, Elokim (which is nature in Gematria) is pressing us and wishes to raise us, and we are seemingly resisting it with a golden calf, celebrating and rejoicing.

When the point in the heart appears, it collides very powerfully with the egoistic desire that has broken out once more. That collision is the shattering of the tablets.

The collision is between the point in the heart—through which we desire to rise and cling to the upper one, to a higher degree, to discover worlds, infinity, and be in a realm of bestowal—and the revelation that we are actually at the point of being a golden calf. We cannot tolerate that contrast, and as a result, all the elements in which we were previously in Kedusha (holiness) shatter.

Those who sinned in the calf were sentenced to death. Subsequently, Moses called, “Whoever is for the Lord, come to me!” (Exodus, 32:26). This is the correction of the desires that have appeared now, that are connected to the golden calf, and with which it is impossible to continue.

Following the correction of all the other desires—the three thousand discernments that Moses killed—he ascends to Mount Sinai yet again. Internally, it means that that point within us rises once again and we receive the tablets of the covenant once more. We rediscover Godliness, the Creator, and begin to come down with the second tablets.

Yet, there is a big difference between the first tablets and the second tablets—Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). The first tablets and the golden calf took place on the ninth of Av (11th month in the Hebrew calendar). The occurrence of the first tablets happens from Shavuot to the ninth of Av. Those of the second tablets take place from the ninth of Av to Yom Kippur. Forty days plus forty days are the time frame of correction from which it is possible to continue.

From The Zohar: Half a Shekel

Half a shekel, half a hin, means half a measure. The Vav is the middle between the two Heys because the Vav is the middle line, called “scales,” which weigh the two lights, right and left, being the two Heys, so the left will not be greater than the right. This is why he diminishes the left, so it will not shine from above downward but only from below upward.

Zohar for All, Ki Tissa (When You Take), item 4

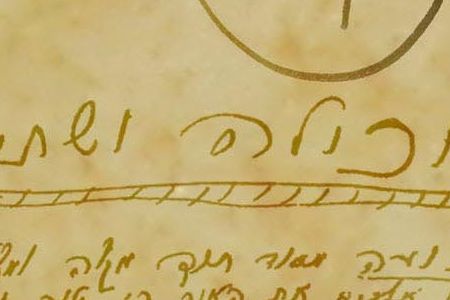

Our big will to receive, the ego, is on the left side. The light, which we can draw if we work correctly, according to the instructions of the wisdom of Kabbalah, is on the right. These are the two Yods, as in the letter Aleph, with the diagonal in the middle as the Parsa (partition) [![]() ]. We must join the light from above, the upper Yod, with the will to receive from below, namely the lower Yod (sometimes written as Dalet, which is Behina Dalet, the Malchut in us, instead of the Yod). The diagonal line keeps the balance between them, thus creating the line.

]. We must join the light from above, the upper Yod, with the will to receive from below, namely the lower Yod (sometimes written as Dalet, which is Behina Dalet, the Malchut in us, instead of the Yod). The diagonal line keeps the balance between them, thus creating the line.

This is why Aleph is the first letter in the alphabet. The portion, Ki Tissa (When You Take), is the beginning of the actual Torah because it engages in the building of the tabernacle and its filling. This is why we must constantly maintain that half, so the right is not more than the left or the other way around. If there is a surplus of desires to receive that we did not correct to the fullest possible extent, then we are not in the desire to bestow. If we take from the will to receive more than we can correct, we are in a state of recognition of evil. It has to be a very precise operation.

Once we restrict all our desires and avoid using the desire in order to receive, but only in order to bestow, we can continue sorting out those small parts of our desire from light to heavy, and join all the corrections to the light.

This is the letter Vav with the punctuation marks, Holam, Shuruk, Hirik, or Kamatz, which is as the Parsa. The light has to be above it because all the corrections are in ascent. In our world—our situation—we will never achieve the revelation of Godliness. There might be various psychological phenomena, but the revelation of Godliness can happen only if we rise above the Parsa.

Following the restriction, once we have the middle line, when we join a group and act in it—as Kabbalists suggest we should—when we try to come out of ourselves and be above reason, above the diagonal Vav, from below upward—we receive the revelation of the spiritual world.

Questions and Answers

Beresheet (Genesis) speaks of the creation of the world. In the desert, things take a long time to unfold, with numerous details along the way, as the portions describe. What do those details symbolize?

The Torah cannot tell us about all that we are going through. It only explains the milestones. It is similar to driving on a road where each mile or several miles are marked by signs.

Why are various garments and a description of the altar mentioned in the desert?

It is the correction of our soul. We have received a system of 613 desires, and each of them consists of all the others, and all are connected. That system is completely broken. It is as though we were given an electronic or mechanical device that is completely broken and we have no clue how to fix it. We would look at it dumbfounded without knowing how to approach it.

This is why we are taught how to do it: “Look at this, fix that, than this, but first that.” There are so many details in our soul, and all of it must become similar to the Creator in its inner structure, in how it works. And although it is the opposite substance from the Creator, “existence from absence,” it must come to resemble the “existence from existence.”

We cannot understand how important our world is, with all its complexities and myriad connections, every atom and every cell in the universe. This is why there are so many details in the correction of the soul. One who walks this path takes part in it and discovers it, and it arouses immense excitement and a sense of harmony and fulfillment.

How do you explain that everything exists and happens simultaneously—the point in the heart is on Mount Sinai, the highest connection, while other desires in me are building a golden calf?

This is the detachment within, where the Moses in us disappears. When Moses disappears we lose contact with the Creator, as this is the only point that connects us with Him. As soon as we disconnect, we find ourselves immersed in our desires, falling into the golden calf. These are the Kelim (vessels) we have taken out of Egypt, Kelim that want the light of Hochma (wisdom), namely pleasure for ourselves alone.

How come the desire obtains contact with the upper force and promptly afterward falls into connection with the golden calf?

There are no delays. There is either Kedusha (holiness) or Klipa (shell/peel). There are no in betweens. We must get used to constantly being in one of the two states; there are no others in our world.

Are Moses’ ascents and descents on Mount Sinai the ups and downs we are talking about?

It is about alternating revelations and concealments. It is similar to the festival of Purim and the story of Esther, who is also revelation in concealment. There cannot be revelation if it is not preceded by concealment. Had Moses not ascended Mount Sinai there would have been no golden calf. But without the golden calf we would not know what to correct. This is how we always progress, on two “legs.”

[1] Babylonian Talmud, Masechet Kidushin, 30b.

[2] Midrash Rabah, Eicha, “Introduction,” Paragraph 2.

[3] Jerusalem Talmud, Seder Nashim, Masechet Nedarim, Chapter 9, p 30b.

[4] Psalms 49:13

[5] Zohar for All, Pinehas, item 247.

[6] Babylonian Talmud, Masechet Gitin, p 43a.